Japanese schoolchildren during the pandemic

American soldiers in Kansas infected with the virus

U Tun Shein with U Pu and U Ba Pe

1918 - 1920

The 1918-20 Spanish Influenza in Burma

In the later years of the 1910s, Burma was in a period of intense political change and debate. World War One ended in 1918 and later that year and the British government promised limited self-rule to India. Though Burma was then a province of British India, London had decided to exclude it from the coming constitutional reforms. The Burmese were incensed. By 1920 a new nationalist movement was growing in strength, inspired in part by the Indian National Congress under Mahatma Gandhi and by Sinn Fein in Ireland. The university boycott in late 1920 forever changed Burmese politics.

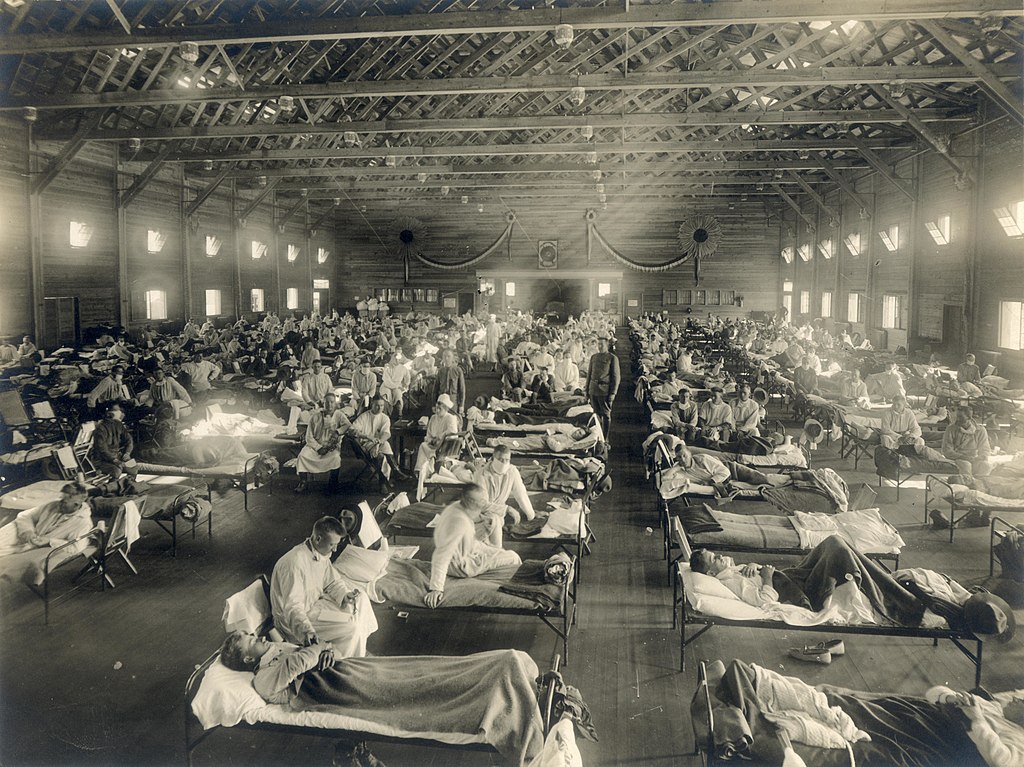

What many accounts of this period usually omit is that all this was happening at the same time as a global pandemic of catastrophic proportions. Between January 1918 and December 1920, the Spanish flu killed approximately 50 million people (estimates vary from 17 to 100 million), including hundreds of thousands in Burma (see below). The Spanish influenza was an H1N1 virus and the deadliest pandemic by far of the 20th century. The disease likely originated in the United States, though no one knows for sure. It was first observed at a military barracks in Kansas in the American mid-West in early 1918. Over the coming months the disease spread to the battlefields of Europe and then around the world. By June the first wave had reached Rangoon. The second wave which began in late 1918 and was far deadlier than the first. India was hard hit, with the number of people dying there from the flu estimated at up to 20 million. Globally, the flu killed between 1-2% of the world's population.

Estimates by scholars suggest that in Burma about 2-3% of the country's 12 million people (up to 400,000 people) died during the pandemic. One valuable background resource on the topic of public health in Burma at the time is Disease and Demography in Colonial Burma by Judith L. Richell, a scholar who analysed census data and found that colonial Burma experienced relatively high rates of mortality. She also noted the problematic nature of colonial-era data and estimated that between one-quarter to one-third of all vital events in Burma went unrecorded, with the registration of births and deaths being a haphazard process.

In early 1918, when the disease was already tearing through Europe, there was no local preparation in Burma. When the pandemic struck, the impact was devastating. Poor urban populations, including Indian migrants, were particularly badly hit. But so too were ordinary villagers. Agriculture in many parts of the country by 1918 was virtually paralysed. In the frontier areas, where there were many returning soldiers, people received no medical attention and it is impossible to know how many died.

One of those who died was U Tun Shein, a leader in the Young Men's Buddhist Association (YMBA). Together with U Ba Pe and U Pu, he was part of the delegation sent to London to discuss Burma's future constitution. The men spent six months in London at the height of the pandemic in 1919. U Tun Shein died shortly after his return to Rangoon. His funeral became a big nationalist affair. A recording of the funeral by U Ohn Maung of the new Burma Film Company, became Burma's first movie and was shown in 1920 to sell-out audiences at the Cinema de Paris (today the site of Bogyoke Aung San Market).