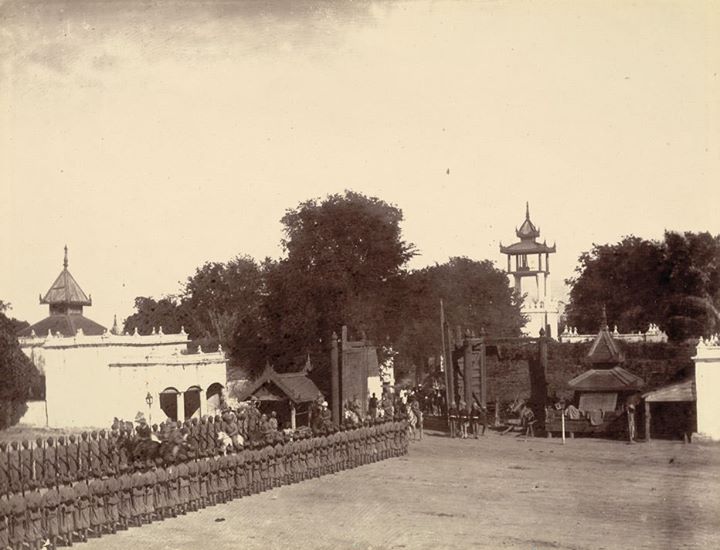

The gates to enter the inner enclosure.

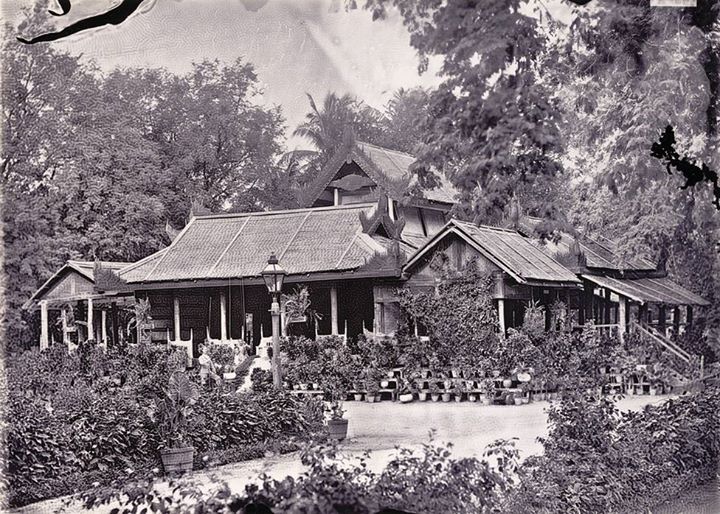

Summer House in the southern garden where King Thibaw formally surrendered to the British.

29 November 1885

After the Burmese Kingdom fell into British Hands

people Kinwun Mingyi King Thibaw Lord Randolf Churchill Yaw Atwinwun Wetmasut Wundauk Sir Harry Prendergast Sir Charles Bernard Prince of Nyaunggyan

From 1883-85, the reformists around the king, led by the Kinwun Mingyi, the Yaw Atwinwun, and the Wetmasut Wundauk, were unable to implement the sweeping changes they felt necessary to save the kingdom. Conservatives, supported by factions within the army and the royal establishment, had pushed back and halted many of the constitutional and fiscal reforms originally set in motion. Fast mounting external and domestic challenges, compounded by worsening economic conditions, fighting in the Kachin Hills, two successive years of drought, and unprecedented levels of migration had led to growing social unrest.

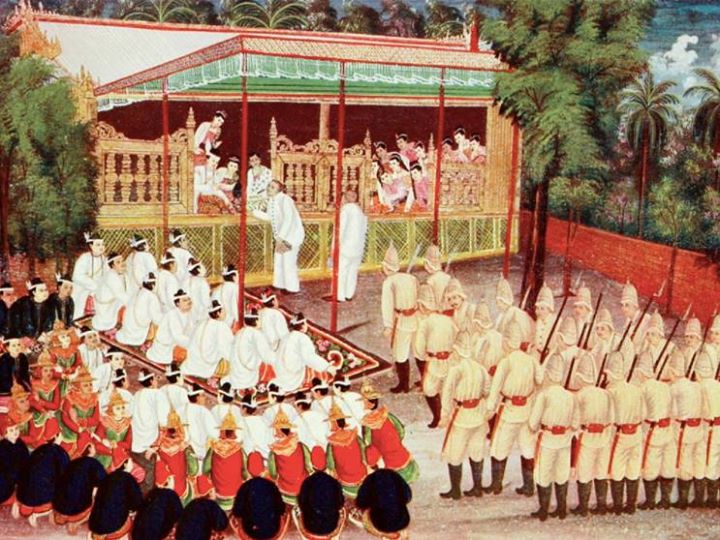

On 29 November 1885, King Thibaw formally surrendered his kingdom to Sir Harry Prendergast from the verandah of his summer house in Mandalay. The British government and its Secretary of State for India Lord Randolph Churchill were certain they wanted to end Burmese independence once and for all. But they were far from certain exactly what they wanted to do with their new possession. The aim was to end French intrigue, stabilize the countryside (which was then partly in rebellion), open a backdoor to Chinese markets, exploit Burma's fabled ruby mines, forests and oil fields, and protect India's eastern flank.

But the British quickly found themselves facing fierce and unexpected resistance, led in part by the aristocracy. The invasion and overthrow of the monarchy was easy, the pacification would take years, and 40,000 extra troops. Leaders of the resistance were executed by the dozen, villages were razed, and a man-made famine led to the deaths of tens of thousands of others. There was still then the idea of placing another Burman prince on the Konbaung throne under a British protectorate, as in Hyderabad or Manipur. When this was found "impractical" (in part because the preferred candidate, the Nyaunggyan Prince, had just died in Calcutta), Sir Charles Bernard, Chief Commissioner of British Burma, considered a form of indirect rule by keeping the Hluttaw as a Council of Ministers headed by the Kinwun Mingyi and local ruling families (myothugyis and saophas) intact.

In February 1886, however, the British opted to abolish the Hluttaw, together with other royal institutions, much to the dismay of the Burmese aristocracy. Over the next year the even more fateful decision was made to rule all of "Burma proper" directly, but the hill areas (the Shan states, Chin and Kachin Hills which were not part of the old kingdom) "indirectly" through their own hereditary chiefs. The two areas (now the 'Regions' and 'States') would have very different colonial experiences leading to very different local perspectives and big problems by the time independence was regained in 1948.

It was not until 1890 the British gained full control over the whole of Upper Burma. By then, ideas of a protectorate were put aside, all traditional institutions of government had been abolished (other than in the hills), and Burma was annexed to the empire as a province of India. All new military-bureaucratic institutions were imported from Calcutta. The rest, as they say, is history.

The illustration shows Sir Charles Bernard, Chief Commissioner of British Burma, entering Mandalay palace for the first time in December 1885.

Explore more in Late Konbaung Myanmar and the English Wars (1824-1885AD)