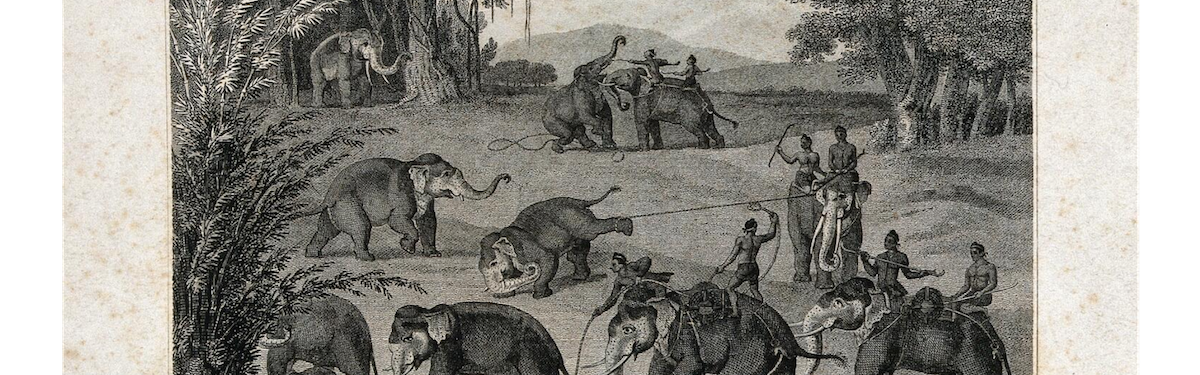

The Elephant Hunt by Singey Bey, presented as a Gift to King Bodawpaya

21 February 1795

An unknown Indian Artist who painted pre-Colonial Myanmar

room Myanmar

By the end of the 18th century, British colonial power had gained a foothold on the western coast of India and the armies of the British East India Company (EIC) were beginning to penetrate deep into the Indian Subcontinent via alliances and wars with the local Indian princes, rajas and nawabs. The British began sending diplomatic missions to the Konbaung king at Ava (Innwa) from their headquarters at Calcutta and Madras across the Bay of Bengal in an effort to secure trading concessions and to establish themselves as the successors to the Mughal emperors. Moreover, since the fall of the Arakanese Kingdom to the Burmese in 1784, Arakanese refugees had been using British Bengal as a base to stage cross-border raids against the Burmese, and Burmese troops had pursued them back across the border, angering the British. Diplomacy was necessary to restore order to the region.

The names of the Scots and Englishmen who led these diplomatic missions — Cox, Symes, and Crawfurd — are all well known, but lesser-known are the identities of the Indian soldiers, translators, artists, and scribes who accompanied them and served as cultural intermediaries between Burma and India, thus making British colonial diplomacy possible. For instance, when the emissary Michael Symes departed Calcutta on 21 February 1795 on his mission to the Court of Ava, he was accompanied by “a havildar (native sergeant), naick (native corporal), and 14 Sepoys (Indian soldiers) with an Hindoo pundit (Professor of Hindu learning), a moonshee (A Mussulman professor of language), and inferior domestics of various descriptions” (Michael Symes, An Account of an Embassy to Ava). Altogether, the mission comprised some 70 people, British and Indian, crammed together aboard the tiny deck of the cruiser Sea-Horse.

One of those onboard that day was the skilled Indian botanical artist Singey Bey, for whom the only documents attesting to his existence are the beautiful watercolors and drawings of Myanmar’s exotic flora and fauna reproduced as illustrations in the journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal and Michael Symes’ An Account of An Embassy to the Kingdom of Ava (1801). Attempting to trace Singey Bey’s biography now, almost 226 years later, is extremely difficult. The first part of his name, Singey, suggests that he was perhaps a Sikh or Rajput (Singey being a corruption of singh meaning “lion” in Hindi, a common Punjabi name) while the second part of his name, Bey, suggests that he or his family had perhaps been in service to the Mughal emperors (Bey coming from the Turkish bayg meaning “lord”). He was likely one of a number of “company artists”, Indians trained in the art of botanical drawing and the science of Linnaean classification who were hired by the EIC to record whatever peoples, plants, and animals that the EIC armies encountered (the exploitation of which might one day fill the coffers of the “Honourable Company”).

At the time, Singey Bey was working under the authority of the soon-to-be famous botanist Dr. Francis Buchanan. Buchanan had studied medicine at the University of Edinburgh and then began his career as a ship’s surgeon and later a doctor in the service of the EIC. But he soon found himself drawn to the Calcutta Botanical Garden which had been founded in 1787 and later developed by the botanist William Roxburgh. Buchanan’s knowledge of plants made him the perfect person to describe the botanical landscape of Burma as a member of Symes' expedition to promote trade with the Burmese king, Bodawpaya, and Singey Bey, who was introduced to Buchanan via Roxburgh, was the perfect person to paint it.

Many artists like Bey came from the Court at Lucknow to which they had decamped from Delhi after a Persian army sacked the city in 1739. Now in the service of the EIC, these artists were part of a larger European enlightenment project to catalogue the entirety of the known world. In India it was driven by the colonial hunger of the British to dominate the lucrative textile and spice trades of maritime Asia. Indeed, the unspoken goal of Symes’ mission was to secure a steady source of teak-wood from Burma for building the Company’s war and merchant ships (eventually, the British would violently conquer all of Burma in order to secure the teak trade). In this way, science and war were two sides of the same colonial coin.

But the company painters were also clearly independent individuals who engaged intellectually with the strange new worlds into which they ventured. Bey’s artwork is intricately detailed and includes images of pagodas, royal officials, barges, and elephant hunts, vividly capturing a pre-colonial Burma on the cusp of immense cultural change. His work blends Indian and European artistic techniques in what came to be known as the “Company Style” (in Hindi kampani kalam). The pictures were meant to depict Burma to European (and Indian) audiences as a remote forest world on the edges of Mughal India ruled over by an all-powerful Buddhist king who controlled the produce of the forest — gems, elephants, teak and gold — and many of Bey’s pictures focus on the Buddha image and Buddhist cosmology, emphasizing the deep faith of the country and its people. His artistic talent was so renowned that even King Bodawpaya asked for one of his pictures, that of the elephant hunt, as a diplomatic gift.

Bey’s pictures were some of the first images of Burma ever seen in Europe. As such they were early steps (along with Buchanan and Symes’ work) in the long project of separating Buddhism from Hinduism in the European imagination. In late 18th-century Burma, the Burmese royal house patronized Brahmins, performed pujas, and worshipped Shiva’s lingam. As Symes writes in his account, “the Birmans, notwithstanding they are Hindoos [Hindus] of the sect of Boodh [Buddha], and not disciples of Brahma, nevertheless reverence the Bralimins [Brahmins], and acknowledge their superiority in science over their own priests or Rhahaans [Yahans or Bikkhus].” This would seem to suggest that Buddhism and Hinduism were not exclusively defined in Burmese society at the time but, increasingly over the course of the 19th century, and with the annexation of Burma as part of the British Indian Empire in 1886, the line between Hinduism and Buddhism became more clear-cut. All in all, for his vivid images of Burmese nature and Buddhism in Myanmar, Singey Bey remains one of a number of fascinating early Indian visitors to the country, the stories and legacies of which remain to be re-discovered today.

Explore more in Early Modern Myanmar and its Global Connections (1510-1824AD)