March 1871 - 1872

First Burmese embassy to Europe

room United Kingdom

people Kinwun Mingyi King Mindon Queen Victoria Prince of Kanaung

On a hot and sticky March morning, the SS Tenasserim, flying the peacock flag of the Burmese kingdom as well as the Union Jack, steamed down the Rangoon River and into the salty waters of the Indian Ocean. It was a new state-of-the-art ship, built in Glasgow for the Henderson passenger line, and came with no less than twenty well-appointed first-class cabins. On board was a delegation from the Court of Ava, led by the scholarly Kinwun Mingyi, a minister of the king’s, destined for England and for what he and his companions knew was their country’s last best chance at preserving its centuries-old independence.

It wasn’t just a short trip in the manner of today’s diplomatic missions. The Kinwun and his team would remain in Europe for more than a year, mainly in England but with side trips to other parts of the British Isles as well as to Rome and Paris. Their hope was for a direct treaty between their king and Queen Victoria, which in their minds and those of the Burmese government would elevate them above the princely states of India and would serve as a guarantee against future aggression. But in visiting the West, the Kinwun also saw for himself the great gulf that had grown up between his country and contemporary Europe, not just in science and technology but in so many other things as well. What he saw and heard influenced him deeply and, through his writings, influenced others at Mandalay as well and would ultimately lead to change and to tragedy.

The Kinwun was then fifty years old, having been born just before the First Anglo-Burmese War in a small town appropriately called Mintainbin (“The King’s Advice”) along the Chindwin River, not far to the northwest of Ava. He had followed a classical education, studying at the Bagaya Monastery at Amarapura, and developed a reputation as a first-rate scholar and poet. He was from the military caste, but he was destined for a softer career, entering first the establishment of the prince of Kanaung and then Mindon’s own service as a gentleman of the household and later as a chamberlain. When Mindon came to the throne, he appointed the Kinwun his privy treasurer and raised him to the nobility. From then on his ascent up the court ladder was assured. He rose to become the governor of Alon, the chief secretary to the Council of State, and finally a minister in his own right. Along the way he was tasked with studying the designs of ancient capitals and submitted detailed plans for the creation of Mandalay. During the 1866 rebellion, the Kinwun had been a significant help to Kingn Mindon and the grateful king had now asked him to take on this most important of tasks - a diplomatic mission to Europe.

Accompanying the Kinwun were three other royal envoys. The first was Maha Minhla Kyawhtin, a junior minister, selected for his American mission school education and his knowledge of English. The second was Maha Minkyaw Raza, an aristocrat of partly Portuguese or Armenian background, educated at Calcutta and then in Paris at the École Centrale des Arts et Manufactures. Europeans who knew him praised his polished and winning manner; he was perhaps the most Westernized of all the Burmese at court, often wearing French dress, and he was even the subject of a brief poem by the Kinwun (such was the literary bent in those days of the Burmese ruling class in those days), admonishing him for giving up his Burmese habits and for having taken a wife in Paris. The last envoy was Naymyo Mindin Thurayn, a scion of an old aristocratic lineage that traced its ancestry back to courtiers of the old Ava dynasty, a graduate of the French military academy L’École Saint-Cyr and destined for a short career in the Cassay (Kathe) Horse regiment of the soon-to-be-extinct Burmese cavalry. And rounding out the team, was a Mr. Edmund Jones, a “merchant of Rangoon” and king’s consul.

Their ship sailed over the dark blue waters of the Indian Ocean, around Ceylon, and then through the Suez Canal and on to Cairo, where they marveled at the Pyramids. They also approved of what they saw as the Western-style administration of Egypt. In Italy, their first stop on the European continent, they were treated to a grand parade and an audience with King Victor Emmanuel before venturing on as tourists to Pompeii. The Kinwun described the ruined ancient city in detail and noted that through such excavations “people of modern times can learn how wise and advanced their ancestors were.” He said: “This is the habit of all Europeans – to endeavor always to discover and preserve ancient towns and buildings.” In general the Burmese envoys were impressed with newly unified Italy and saw in the Italian progress of the time something that Burma might usefully copy.

They went onward through Florence and the south of France and Paris (where they stopped to have a look at Napoleon’s tomb) and arriving at Dover on 4 June. There, the envoys received a very pleasant welcome from British officials (“we can never forget Dover until the end of our days”) and left in special carriages to a nineteen-gun salute as ordinary people waved and cheered from the sidewalks and their houses. Finally in London, they took up rooms at the Grosvenor Hotel, and Jones set about hiring the appropriate carriages and outriders, footmen, waiters, and messengers, all in special livery for the new embassy of Burma.

The next few weeks were a whirlwind tour of late Victorian society. First it was Ascot on a bright and sunny June day, where the Kinwun and his compatriots noticed that the Prince of Wales “was wearing an ordinary suit and moved about the crowd, speaking freely with everybody, without assuming the airs of a prince, as if he were an ordinary lord or a commoner.” All along the way people had cheered them on, and they had bowed and nodded in return. The envoys were warned such bright and sunny days were rare in England. They visited “a school where 700 young boys were not only taught, but also clothed, lodged and fed,” and they went with the lord mayor of London to the Tower of London, “where we saw the dungeon and the place where traitors were executed,” and then to a reception at the Kensington Museum. On another day they went to see the country home of the duke of Devonshire, listened to a concert, and enjoyed a five-course meal at Westminster with various members of Parliament.

The Kinwun and his colleagues also visited Madame Tussaud’s, where they saw figures of people they had seen in real life, such as the Prince of Wales. As the Kinwun looked into a hall full of wax figures and visitors, he noted in his diary that he “found it difficult to differentiate between the lifeless wax figures and the human beings.” They were given a book about the museum, which they looked through together back at the hotel. When they visited a charity bazaar at the home of the earl of Essex, the earl took them inside and showed them “a painting of a monkey which had been bought by his parents for 40,000 rupees.” They attended that year’s Eton and Harrow cricket match, toured Middlesex Prison, spent an afternoon at the Crystal Palace, and walked around the “clean and tidy” casualty ward at St. George’s Hospital. Then it was Bethlehem Mental Asylum, where “patients were cared for in very pleasant surrounding.” Over the next week the team visited Westminster Abbey, went on a boat trip up to Hampton Court, and saw the exhibitions at the British Museum. On a hot July evening, “as hot as any October day in Burma,” the envoys had a chance to repay some of the hospitality shown by throwing a reception on board the royal ship.

For the Kinwun (less so for the others who had already spent time in the West) all this was eye-opening. If he had any doubts before the trip that Burma could resist future Western aggression, he would only have more now. The gap, not only in science and technology but in so many aspects of society and political life, was plain to see. Until the fall of the kingdom the Kinwun would counsel restraint and compromise with the British; he would also be on the side of those pushing for ever more radical reforms within the palace walls. But for now he still had his mission, a treaty with the queen.

On 21 June the mission was received by Queen Victoria herself at Windsor Castle. Dressed in their most gorgeous silk and velvet robes, they traveled in excited anticipation on the royal train and were met at the little station outside London by the queen’s lord chamberlain, Viscount Sydney, and three state coaches. In the castle they noted that the queen stood up to receive them (“the European way of showing the deepest respect”), and the Kinwun handed the queen a casket containing the royal letter of greeting and the boxes of gifts.

“Is His Burmese Majesty, the King of the Sunrise, well?”

“His Majesty is well, Your Majesty.”

“Did Your Excellencies have a pleasant journey to England?”

“We had a pleasant journey, Your Majesty.”

It wasn’t much more than that, and the envoys were disappointed that they had been presented to Victoria not by the foreign secretary but by the duke of Argyll, the secretary of state for India. But they hoped this was a start, and after a final walk around the castle, it was back to the Great Western Station and the Grosvenor Hotel for a rest. That evening the Kinwun and his aides were invited to a state ball at Buckingham Palace, “where members of the royal family, their friends, ambassadors of foreign countries and their ladies, lords and dames, high officials and their wives romped, danced and made merry.”

A big part of their time in Britain was also spent meeting with the various chambers of commerce, whose real interest was not so much Burma itself but Burma as a back door to the fabled markets of China. A China-Burma railway seemed to hold the key to untold fortunes. The Kinwun visited Manchester, Birmingham, Leeds, and several other industrial cities, touring factories and meeting with local businessmen, and at each place the interest in China loomed large. Crowds of curious people followed the envoys everywhere, and at the Lime Street Station in Liverpool nearly two thousand men, women, and children greeted the embassy as they arrived on the six o’clock train from Birmingham.

The Kinwun tried to impress the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce with Burma’s potential. It was a way of describing the country that was to be often repeated over the next century.

Our land is fertile and richly endowed with minerals and raw materials. We have great mines of rubies and other precious stones. Our teak has no equal in the whole world. European visitors marvel at our gushing oil wells. We have also iron and coal. We produce gold and silver. Our land produces enormous amounts of sesame, tobacco, tea, indigo, all kinds of paddy, all kinds of wheat, and all kinds of cutch. We are glad to note that western nations agree with us that the time has now come to develop this rich country.

By this time the notion that the Burmese king was somehow a hindrance to opening backdoor a backdoor trade to China was gaining currency, and at Halifax the Kinwun took pains to make clear that Mandalay was not at all opposed to a railway to China but that the routes suggested thus far were impossible to follow as they would pass wild and desolate areas where the terrain would challenge even the most modern engineering.

At Glasgow, after a visit to the stock exchange, they were hosted to a lunch at the town hall with three hundred merchants. This was the home of many of Rangoon’s primarily Scottish business community. The president of the Chamber of Commerce said: “We must be truthful and say that the commerce of the Burmese kingdom of the past few years has not progressed at all, because of many difficulties and hindrances, and only when the Burmese King is prepared to remove those difficulties and hindrances, will the two kingdoms really benefit.”

The tour continued on. On 26 September they crossed the Irish Channel, and took the train to Dublin, where they stayed at the Shelburne Hotel and visited St. Patrick’s Cathedral as well as the “great teaching school of Dublin” (Trinity College). For evening entertainment, their Irish hosts organized a show that included a pair of Siamese twins and dances by a couple of dwarfs. As heavy rains fell, they traveled through the countryside; the Kinwun noted that there was very little cultivation and that the soil in Ireland seemed much less fertile than in England, consisting only of “marshy lands, dark brown in colour.”

At a private observatory in Newcastle, the Kinwun was interested to learn that the moon was covered by deep valleys, that its water boiled, then froze during alternate weeks, and that there were no living creatures. And at Holyrood, in Edinburgh, the Kinwun and his colleagues gazed at the portraits of the Scottish rulers, and the Kinwun expressed particular interest in the “tragic history of the beautiful Mary Queen of Scots.”

All this was wonderful, but after months of traveling around, there had been only one audience with the queen and no sign that the British were at all interested in a treaty. Back home Mindon was fast losing patience, and in November he ordered the Kinwun and the others to Paris, a veiled warning to London that Burma had other friends and in the hope of finalizing a new commercial treaty with the new French republic.

But in Paris there were sights to be seen as well, even amid the destruction of the recent Franco-Prussian War. These sights include the Louvre, where they marvelled at the collection of weapons, the Japanese silks, and the Egyptian mummies, and at the National Library, where the Kinwun was startled to find an old map that included Burma and was apparently drawn by Marco Polo at the time of Pagan. This, he said, made him realize “that Europeans had been visiting Burma for so many centuries.”

Then, as Christmas approached and under their very first snowfall, the team trekked up to Versailles, where they met the French president and signed a commercial treaty. It was the beginning of a Franco-Burmese relationship that in practice came to little but that would soon encourage the British to imagine the worst and decide to end the Kinwun’s kingdom.

~Adapted from ‘The River of Lost Footsteps’ by Thant Myint-U.

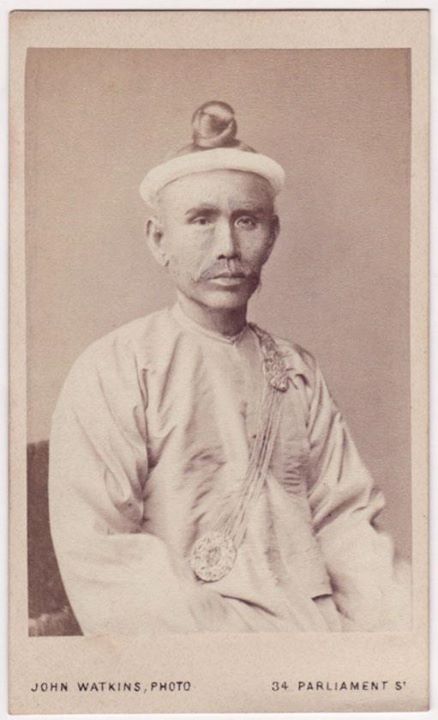

The photograph shows the first Burmese embassy to Europe. Seated from left to right: Royal Secretary Naymyo Mindin Thurayn Maung Cheint; the Pangyet Wundauk Maha Minkyaw Raza Maung Shwe O (educated in Paris); Chief Minister the Kinwun Mingyi (leading the embassy); the Pandee Wundauk Maha Minhla Kyawhtin Maung Shwe Pin (educated in Calcutta); and standing in back: Major A.R. McMahon, British Agent at Mandalay and Edmund Jones, Burmese Consul at Rangoon (both fluent in Burmese).

Explore more in Late Konbaung Myanmar and the English Wars (1824-1885AD)