Sir Joseph Augustus Maung Gyi

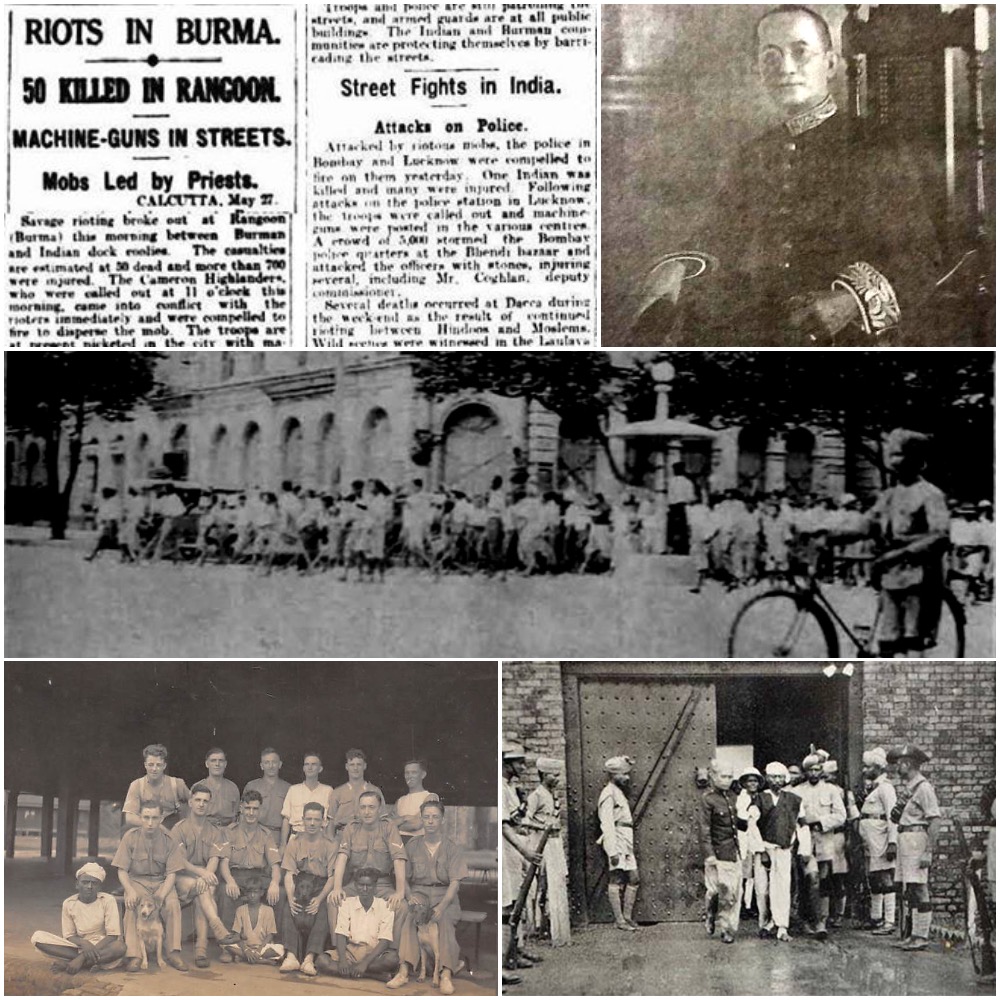

1930 Communal Riots

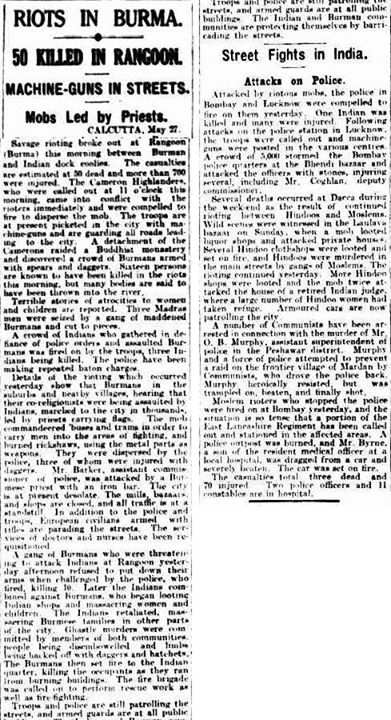

1st Battalion Cameron Highlanders

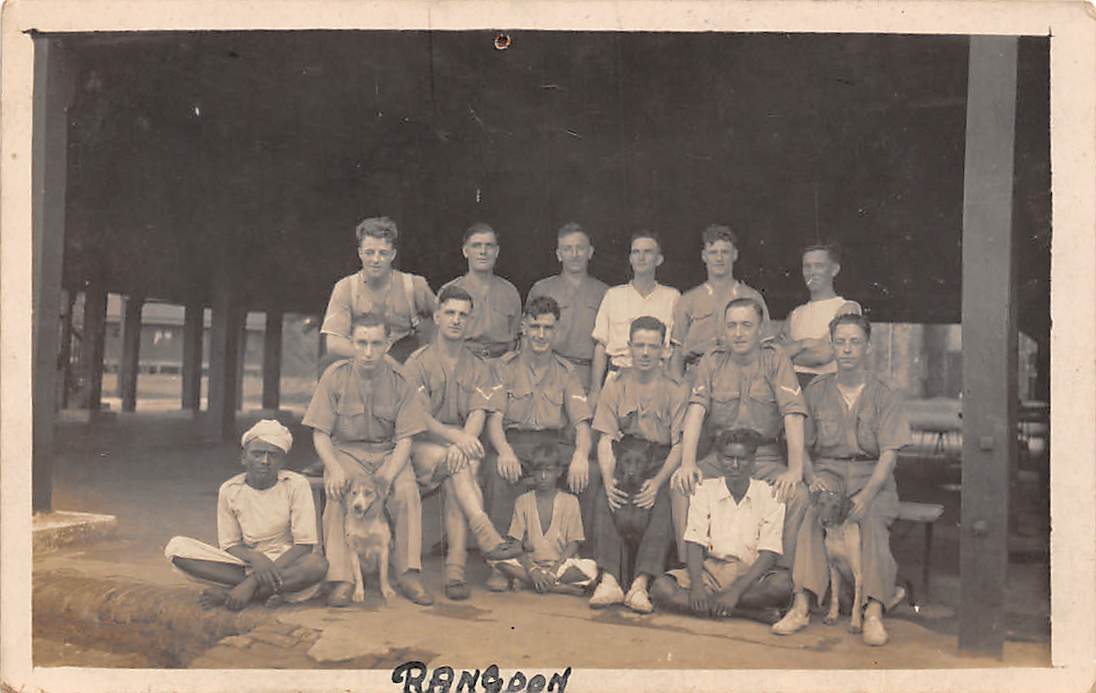

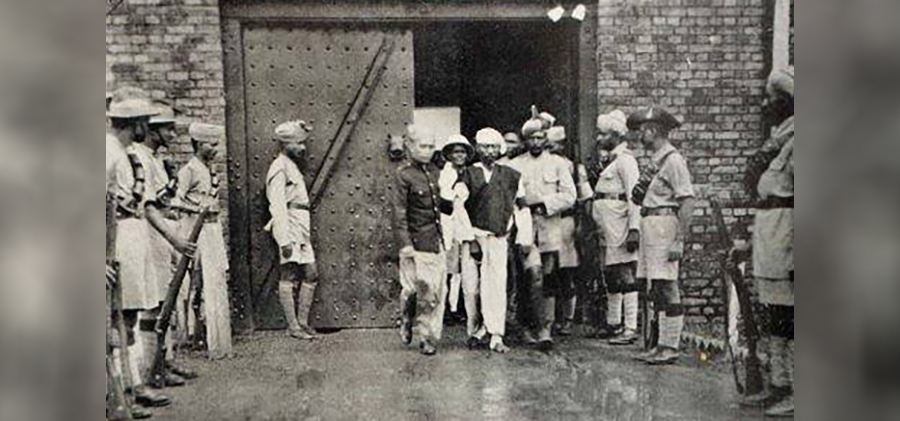

Saya San being led to the gallows

1920s - May 1930

From the Great Depression to Riots and Rebellions

In the 1930s, Burma was in crisis. Burma was then a province of British India. Under a new "dyarchy" system, the government included ministers chosen by the Legislative Assembly, which included both elected and non-elected Members. Elections had been held in 1922, 1925, and 1928 and were contested by an array of new political parties. The focus of all the political parties was constitutional change and "home-rule".

At the same time, life for ordinary people was going from bad to worse. Under British rule, the efforts under kings Mindon and Thibaw to grow local industries had been stopped. Instead a new political economy was established, one which depended on the export of primary commodities, controlled by just a few foreign companies, and the import of cheap labour from India. A few big rice export companies monopolised trade, colluding with one another to keep prices low for Burmese farmers.

By the 1920s, pre-colonial social structures had collapsed. Crime soared. Burma then had one of the highest rates of homicide in the world. The jails were overflowing, with a bigger proportion of people in jail (almost all young Burman-Buddhist men) than anywhere else in the British Empire. Dacoity also spread throughout the country, together with movements to resist the payment of taxes. Few had access to modern healthcare. A pandemic early in the decade had killed as many as 400,000 people. Corruption was rife as well, including in the police. By one estimate out of six hundred magistrates, only fifty could not be bribed. For many ordinary people, life was bearable, but they were forced to take on more and more debt to survive.

It was into this context that the Great Depression struck Burma in 1928-1930. Rice prices quickly collapsed making it impossible for millions of farmers to service their debt and pay taxes. Two million acres of farmland, mainly in the Irrawaddy delta, fell into the hands of Indian (Chettiyar) money-lenders. Poor Indians also lost their jobs – as mines and factories closed down - and many were unable to return home.

By 1930, hundreds of thousands of poor Burmese and poor Indians were competing for the low-wage jobs that remained. On 5 May, a 7.3 Richter earthquake and destroyed dozens of buildings in downtown Rangoon and toppled the Shwemawdaw pagoda at Pegu. In late May 1930, communal violence erupted in Burma for the first time, leaving at least 120 dead and 900 wounded in Rangoon. Fighting between (mainly Telegu-speaking) Indians and Burmese dockworkers had spread quickly through the city, with many innocent men, women, and children hacked to death over nearly two weeks of violence. Those who fought each other and those who died were those at the very bottom level of the economy and who had been exploited by the colonial economic system for more than a generation.

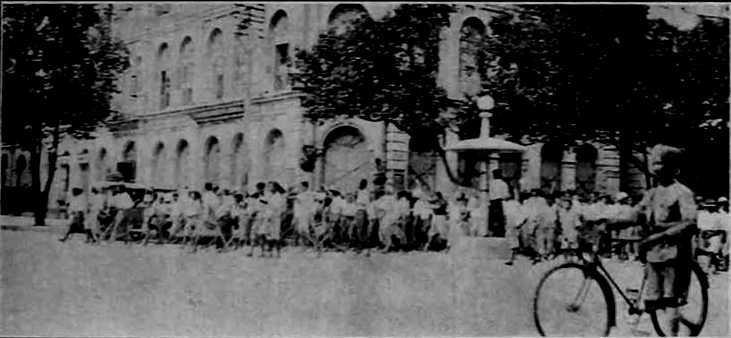

The Cameron Highlanders (a British Army regiment) were brought in to restore order. They set up checkpoints along the Prome Road and other avenues into the city and raided several Buddhist monasteries where they found stashes of weapons. Machine guns were mounted along Fraser and Dalhousie Streets and armed units patrolled all of downtown from Mughal Street east. Only by the second week in June did the violence subside. A couple of weeks later, an uprising in the Central Jail (near St. Johns) led to the massacre of dozens of inmates by the Indian guards and staff, almost certainly a retaliation for the Indian victims of the riots just past.

The country was now simmering with desperation and anger. By late in the rainy season, as economic conditions worsened, villagers begged to be allowed to defer tax payments for a year. The governor at the time was Sir Joseph Augustus Maung Gyi, an Oxford-educated barrister and the first Burman to hold that high office. He toured villages and listened to the pleas of now hunger-stricken people, but refused any deferral or even lessening of taxes. The truth was that Sir Joseph had little real power, which rested in the British controlled officialdom and army. Being Burmese, he was not even allowed in the Pegu Club.

In December, just after another major earthquake, Burma erupted in one of the greatest anti-colonial revolts anywhere in southeast Asia. Led by Saya San (until then a relatively unknown political figure and former Buddhist monk) and his “Galon Army”, the uprising quickly spread from Tharawaddy to many districts from Henzada to Yamethin.

So fierce was the resistance by Burmese villagers that the British had to bring in two fresh army divisions from India. Emergency Powers were promulgated and the media tightly controlled. By the time then fighting was over nine months later, at least 3,000 rebels had been killed, and 8,000 arrested, of which 78 were hanged. Saya San himself was hanged in Tharawaddy Prison on 28 November 1931, exactly 46 years after the British takeover of Mandalay.

Over the 1930s, Burmese politics would take an increasingly radical turn.