1 October 1949 - October 1954

KMT Invasion of 1950

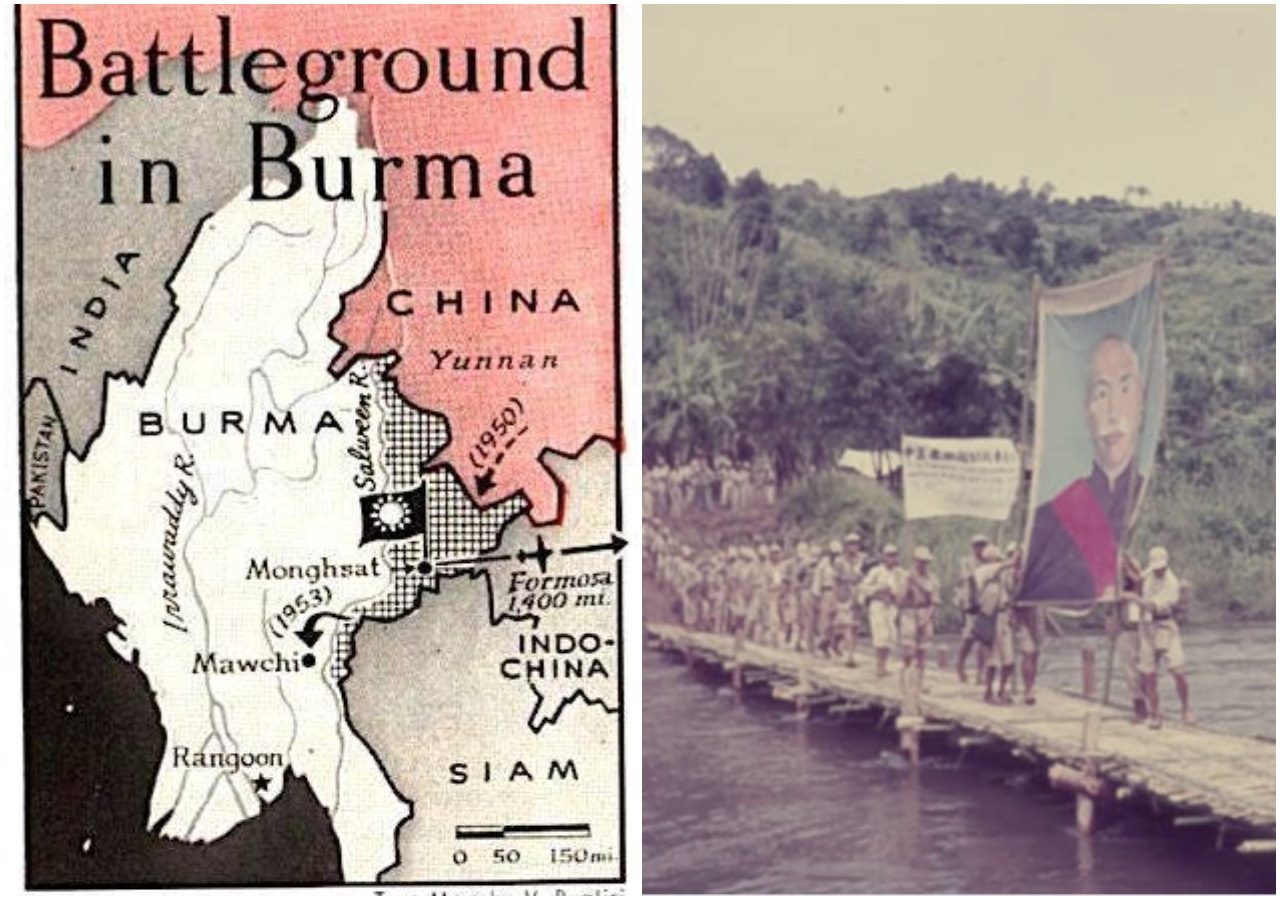

On 1 October 1949, Mao Tse-tung, standing at the gates of the Forbidden City in Peking, formally proclaimed the establishment of the Peoples’ Republic of China. Thousands of miles to the southwest, the beaten remnants of Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist armies straggled across the barely demarcated border along the cloud-covered Wa hills and into the princely state of Kengteng in the far east of Burma. They were led by General Li Mi of the Chinese Eighth Army, and they headquartered themselves at the little frontier town of Tachileik on the road leading down to Thailand. Their strength was about 2,500.

Alarmed at the incursion, units of the Burmese army moved against them in July 1950 and retook Tachileik, swinging around troops from hard-pressed anti-insurgent operations in the center of the country. But the Chinese Nationalists only regrouped at nearby Mong Hsat and began enlisting local Shans and tribal leaders to boost their strength. In an echo of the Ming invaders of the 1640s, their aim was never actually to stay in Burma but to use Burma as a base from which to regain their homeland. For the time being, though, they were there to stay.

By 1953 they had recruited over 12,000 new troops, imposed local taxes, and built an airport at Mong Hsat with regular flights to their fellow Kuomintang (KMT) forces who had fled in the opposite direction to Taiwan. Huge quantities of arms and supplies were flown in together with secret American trainers and other government officials. Soon the KMT took over the whole region east of the Salween River, moving up toward the Kachin hills and down toward the upland areas controlled by the Karens, with whom they made a sort of tactical alliance. In March 1953, they were on the verge of taking all the Shan States and were within a day’s march of the regional capital, Taunggyi.

From the Burmese point of view, this was nothing less than a combined Chinese Nationalist and American invasion, and nothing could be spared in meeting this unexpected threat. Three good brigades were placed under the command of the Anglo-Burmese brigadier Douglas Blake, who then drove the KMT east across the Salween as far as he could until he finally met with fierce resistance near Kengtung.

In April the Burmese lobbied for a resolution in the United Nations General Assembly, calling for negotiations and a withdrawal of the Chinese forces to Taiwan. After a series of meetings in Bangkok the Chinese finally agreed to evacuate 2,000 troops. Though this did take place (using the Air Transport Company of former US General Chennault who had led the "Flying Tigers" during World War Two), most of the 2,000 were young boys, local recruits, and many non-combatants; in addition many of the arms surrendered were antiquated junk. The Burmese were not very satisfied. After so much expectation, they now believed they couldn’t really depend on the UN and in the future would have to learn to defend themselves better: what they needed was a bigger and better army.

Over the 1950s, the Burma Army turned itself from a small politicized and factionalized hybrid force, half British and half Japanese by training, into a more professional and more coherent military machine, loyal only to itself. Martial law in the Shan States, a result of the Chinese invasions, had meant that the army was dangerously overstretched, across multiple fronts and without a clear command and control structure. With everything going on, the War Office in Rangoon was too busy dealing with the day-to-day crises to think in the long term and gain a clear upper hand. General Ne Win was more than aware of the problems and the need for strategy and coordination. In 1951, he established his Military Planning Staff under a group of young colonels, saying that the country was nearly at full-scale war and could no longer wait to undertake the needed reforms. The young colonels quickly set to work.Their analysis was that China constituted the number one threat to Burma and that the Burmese army needed to be able to contain any aggression by Peking for at least three months, after which with a bit of luck, there would be intervention by the Americans under a UN flag.

Reports describing armies around the world – the British, the American, the Indian, the Soviet, and the Australian – suggesting ideas and lessons to be drawn from each, soon circulated within the military. Study missions were sent abroad to learn first-hand what worked best, and shopping trips were organized to Commonwealth countries, Israel, Yugoslavia, and Western Europe, to buy the latest in military hardware. Israel provided inspiration for a civil defense plan, and a new Defense Academy established at Maymyo was modelled on a combination of Sandhurst, West Point, St. Cyr in France, and Dehra Dun in India. In the context of the Cold War, all sides were eager to lend the Burmese officers a hand and compete for as much influence as possible. A psychological warfare directorate was set up. The old War Office became a much more efficiently run Defense Ministry, with only the pretense of democratic control and a reality of airtight and closely guarded army autonomy.

The changes had a big impact. By 1954, the army was able to mount more complex and effective operations against rebels and battlefield opponents of all stripes. The Chinese Nationalists were at first routed near the Mekong River and survived only because they received fresh reinforcements from Taiwan. Another campaign targeted the Karens and forced the bulk of the Karen National Defence Organization (KNDO) forces up into the heavily forested limestone hills along the Thai border. Smaller operations pushed back the communists south of Mandalay as well as the Islamic insurgents in Arakan. Over the months, nearly 25,000 rebels surrendered. In October, U Nu was able to say that the civil war, “which at one time seemed likely to swallow Burma, is no longer a menace to the integrity of the State.” It was quite an achievement.

At the same time, personnel changes altered the balance of power within the army itself, as the group around General Ne Win removed anyone with any possible rival loyalty. Those who had come into the armed forces under the British were quietly retired, and senior positions were increasingly reserved for men of the Fourth Burma Rifles, Ne Win’s original (Japanese-trained) battalion. These same men also staffed the new Defence Services Institute, which first catered to the needs of soldiers but then began running its own businesses at a profit; by the end of the 1950s, it would be managing the Five Star Shipping Line freighter service, the Ava Bank, and major import-export operations like the old Rowe and Co. department store. This further strengthened the hand of the War Office, both over its commanders in the field and over the politicians and civil servants who would otherwise control the army’s coffers. The army even began funding it’s own newspaper, the English-language Guardian, headed by one of the country’s most respected journalists, Sein Win.

This was a time when armies throughout newly independent Asia were coming into their own: in South Korea and Taiwan; in South Vietnam, where the army was being built under U.S. assistance; and in Indonesia, where right-wing officers in 1956 first formulated their dwifungsi ("dual function") doctrine. In Burma, the army was stepping into a huge institutional vacuum, left behind by the collapse of old royal structures, incomplete or ineffective colonial state building, years of war, and then a sudden colonial withdrawal. And this military machine was slowly but surely coming under the control of just one man: General Ne Win.

~ Adapted from The River of Lost Footsteps by Thant Myint-U

The pictures show General Li Mi, who led some 2,500 soldiers of Chiang Kai-shek’s defeated nationalist army across the border from China into Burma in 1949; Kuomintang (KMT) soldiers boarding a plane bound for Taiwan in 1953; KMT soldiers dining, probably in the Thai-border town of Tachileik where they were headquartered; and a KMT child soldier.