Land Categorization

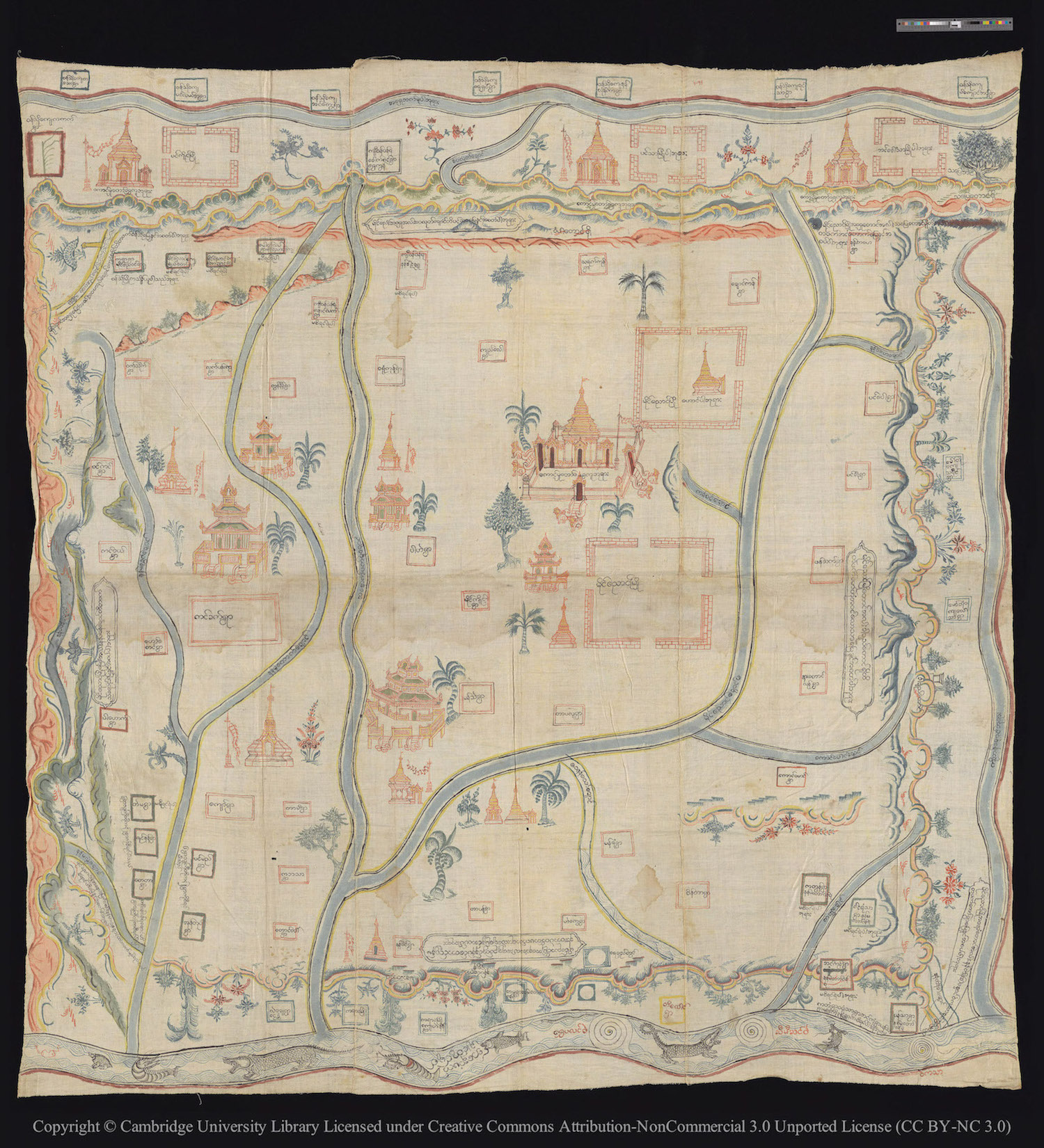

Very broadly, in Konbaung-era Myanmar there existed four main classes of land: crown land, ancestral or allodial land, glebe land, and official or prebendal land.

Crown land (nanzin ayadaw-myay) was the personal land belonging to the king. This consisted of scattered but substantial estates which he had inherited from his ancestors or acquired through marriage, and which were worked by a special class of labourers known as lamaing, or crown serfs. Certain other types of land could also become crown property, such as lands which was difficult to assign to any one person or groups, for example the small islands in the Irrawaddy River near the capital which disappeared beneath the surface of the river every year, and then, on reappearing, could not easily be identified. The right of collecting rent from such land was the responsibility of the Superintendent of Crown Property (the Ayadaw-ok), who was allowed to dispose of them as he thought most profitable, while collecting some sort of commission for himself. Land confiscated for criminal acts (thein-myay, or "confiscated land") and land belonging to owners who died and left no heirs (amwe-son-myay, or "end of lineage land") was also supposed to become crown land if deemed valuable. Thus the king was the default landowner of his realm.

While the king was the largest single landowner, the majority of land was probably ancestral allodial land - boba-baing-myay, in Burmese literally "father’s and grandfather’s land". Land cleared by an individual and kept within the family was classed as allodial in this way; it was not private land as the holder did not have full rights to dispose of the land as he or she saw fit but it was often mortgaged and some parcels may have been bought and sold. Land that was fully private, or pudgalika, did not appear as a distinct category until colonial times.

Glebe land belonging to religious establishments, monasteries and pagodas were crown lands or allodial lands donated by the king or other notables in perpetuity; its integrity was meant to be scrupulously maintained. In fact, glebe land tended to shrink over time, as lapses in record-keeping allowed cultivator-tenants or other local people to claim bits of the estate as their own. Land donations were often accompanied by donations of slaves to work the land; known as hpaya-kyun, they were irredeemable slaves. Though the hpaya-kyun were common cultivators in every other way, they came to occupy the lowest rung of the Burmese social ladder, as low as those who dealt in death; they were considered beyond the pale and no social interaction with them was allowed.

The last and most complicated category of land was official or prebendal land, known as min-myay in Burmese. Min means "ruler" and, in a village setting, might refer to the local chief. Min-myay in this case was the "chief’s land" and was part of his inheritance as head of his lineage. More generally, the phrase might refer to all land seen as belonging to the chiefly clan but this phrase was also used to categorise land granted by a king to his crown servants in return for military or other obligations. In the most simple cases, the king, in establishing a new army regiment, might grant the officer in charge of the regiment an estate near the capital. The officer would then parcel out the estate among his men and their families, setting aside land for their residence (nay-myay), their personal cultivation when not on duty (loke-myay) and for extra income (sa-myay); the officer would doubtless keep the best parts for himself. As office was hereditary, these grants also tended to become hereditary and such land was treated a little differently from allodial land, despite constant crown attempts to ensure the integrity of these estates and the continuity of their prebendal status. Often, crown servants who had fallen into debt would mortgage or even sell their land and thus the original connection of the land to service would be lost.

The distinction between different types of prebendal holdings and between prebendal and allodial land was clear only in theory. In practice, failures of royal information, coercion or will, meant that land nominally attached to office came under the control of the local gentry. For example, confiscated land which should have reverted to the crown might have remained unreported; instead, the land might have been taken quietly as part of the local chiefly estate. At the core of much of the vagueness was the substantial gap between local realities and the idea that the crown controlled land and could assign land at will. This vagueness, manageable and perhaps even desired under old norms and practices, would become problematic with the approach of colonial rule and attempts to rationalise land-holding and revenue administration.

~Adapted from The Making of Modern Burma by Thant Myint-U.

Explore more in Late Konbaung Myanmar and the English Wars (1824-1885AD)