8th Century - 13th Century

Once upon a Time in Dali Kingdom

room China

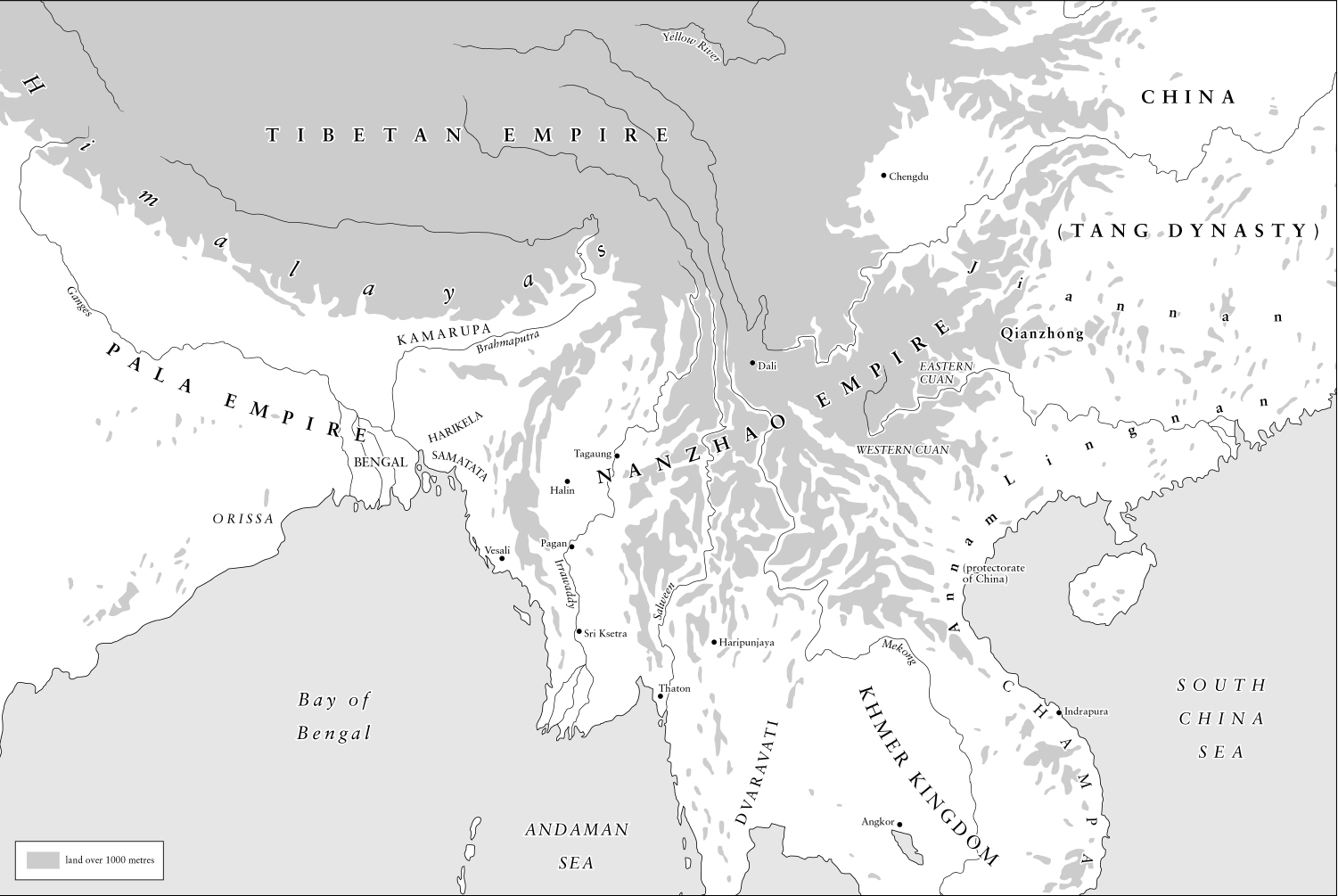

For much of its early history, Burma’s neighbor to the northeast was not China, but the independent kingdom of Yunnan with Dali as its capital. And from the eighth to the thirteenth centuries this kingdom was a power in its own right, at times allying itself with the Tibetan empire to its west, at others, with China’s Tang and Song dynasties to the east. Its mounted armies ventured deep into what is today Burma and may have been behind the founding of the medieval city of Pagan. It is not known what the people of Yunnan called themselves ("Yunnan" itself is a relatively new word) but the Chinese called their ruler the Nanzhao, the Lord of the South, and this became the name of the kingdom as well.

Yunnan came under partial Han Chinese authority in ancient times, but in the third century AD the last of the Chinese garrisons withdrew, leaving Yunnan to its mix of native peoples. Amongst these peoples would have been some of the ancestors of the modern Burmese, as well as the minority peoples of Yunnan today, speaking a range of languages and dialects. In the ninth century, the Chinese ethnographer Fan Cho compiled The Man Shu: Book of the Southern Barbarians, in which he described Yunnan’s different communities. There were, he said, various Wu-man or "black southern barbarians", so-called after their dark complexions. Many were pastoral folk, tending goats and sheep, and slowly drifting southward, along the many river valleys, from the Tibetan marches down to the hot and arid plains of Burma. Some of the barbarians "were plentiful all over the mountain wilds". Others were "brave, fierce, nimble and active [….] They bred horses, white or piebald, and trained the wild mulberry to make the finest bows". Still another group included women who "only like milk and cream" and who are "fat and white and fond of gadding about". To Chinese eyes they were not a particularly hygienic lot, but cheerful nonetheless. One tribe known as the Mo-man were said to live their lives without ever washing their hands or faces: "Men and women all wear sheep-skins. Their custom is to like drinking liquor, and singing and dancing."

From Dali, around the time of the Islamic conquest of Spain, the Nanzhao ruler had unified six nearby principalities into a single state and then had gone on to mobilize these diverse tribal communities. From the start, it was a militaristic state, expanding energetically in every direction. In these early medieval times, eastern Asia was dominated by two great powers: China and Tibet. The Tibetans were the upstart power but at the height of their imperial reach. For some time, Nanzhao fought alongside the equally aggressive Tibetans. In 755, when China was wracked by internal rebellion, the Tibetans and Nanzhao joined together to pillage Chinese cities.

Later, the Chinese managed to break apart the Tibet-Nanzhao alliance. Tibetan expansion was then a big headache for the Chinese court and the Chinese were trying for a policy of continental encirclement, aiming at bringing together the Turks and Arabs to the west, the Indians to the south and Nanzhao to the southeast, in a grand coalition to crush Lhasa. "Using barbarians against barbarians" was a time honoured Chinese creed. When a combined Nanzhao-Chinese army defeated a Tibetan force near the present-day Burmese border, the Tibetan side included captives from as far away as Samarkand and Arabs from the Abbasid caliphate, men from the court of Harun al-Rashid taken prisoner on a Yunnan hillside together with 20,000 suits of armour. In appreciation, the Chinese received Nanzhao’s envoys as representatives of high-ranking kingdom, ahead of Japan, welcoming them with an honour guard of war-elephants and presenting exotic gifts.

The Nanzhao were then at the pinnacle of their power. They invaded south to Burma, plundering the little walled towns of the Irrawaddy valley, and perhaps even reaching the distant and sandy shores of the Bay of Bengal. During a period of supreme confidence, they would even break their pact with China, attacking Chinese-controlled Hanoi, and marching over the mountains into Sichuan and sacking the city of Chengdu. All this from Dali, where the ruler of Nanzhao sat on his throne, swathed in tiger-skins, "red and black with stripes deep and luminous, from the finest tigers in the highest and remotest mountains".

When the Nanzhao dynasty eventually fell it was more because of internal intrigue than external pressure. The whole royal family was wiped out in a power struggle in 902, and was replaced by a slightly more modest regime, still based at Dali. By then, Buddhism had a firm grip on local society and the kings of Dali emerged as committed patrons of the faith. The capital itself became an important center of Buddhist learning. The links with Burma were strong, and the new Burmese kingdom at Pagan most likely developed in the shadow of Dali’s influence. And, via Burma, there would have been ties as well to India, then divided into Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms, on the eve of the Muslim invasions.

The kings of Dali adopted the name Gandhara for their realm - the same word as Kandahar in modern-day Afghanistan and, still to this day, the literary Burmese name for Yunnan. Gandhara was once an almost mythical Buddhist land, straddling the present Pakistan-Afghanistan frontier at the time of Alexander the Great, and was remembered long afterwards as a place of profound scholarship, governed by sages, peaceful and devout sages. The Dali kings even styled themselves as descendants of the great Indian Buddhist emperor Asoka, who had reigned in the third century BC, seeing themselves as part of a fraternity of Buddhist states, from middle India to Ceylon and on to Vietnam.

Dali also associated itself with Mithila, the important commercial and religious center once home to the Buddha himself - the New York of the ancient Indian world, with "store-houses filled, and sixteen thousand dancing girls and treasure with wealth in plenty". Other great Buddhist sites were also transposed, metaphorically, onto the surrounding landscape. A cave on the other side of Lake Dali became the famed Kukkutapada cave (the original is in north India) where the monk Maha Kasyapa is believed to be waiting in a trance for the coming of the next Buddha. Next to the cave is said to be a stupa with relics of Buddha’s great disciple, Ananda, as well as the Pippala cave where the First Council of Buddhism was held. In this way, Dali became a facsimile of the holy land. As with the later kings of Burma, the kings of Dali wanted an Indian pedigree, and claimed descent from that greatest of Indian emperors, Asoka. The Persian scholar Rashid al-Din wrote that the king of Gandhara styled himself maharaja.

A variety of Buddhist schools flourished here. Chan Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese pronunciation, Zen, was a preferred school. Zen had begun in the seventh century within the Chinese Buddhist world as a reaction to the never-ending production line of monastic text, commentaries, philosophical debates, images and rituals that its founders believed were choking off a more practical way to salvation. They hated all intellectualization and systematization and often refused to write anything down. Their sayings were purposely cryptic and their style of teaching known as "strange words and stranger actions". Later, Tantric Buddhism, an import from both Bengal and Tibet, gained the upper hand. Its leaders were the Azhali, originally adepts in yoga and arcane rituals, who were believed to command supernatural powers. In Burma, they would be known as the Ari, infamous for their heterodox ways and sexual licentiousness.

The Yunnan of old was a Yunnan that looked in different directions for ideas and inspiration, a link between China and the Indian world.

~ Extracted from Where China meets India by Thant Myint-U