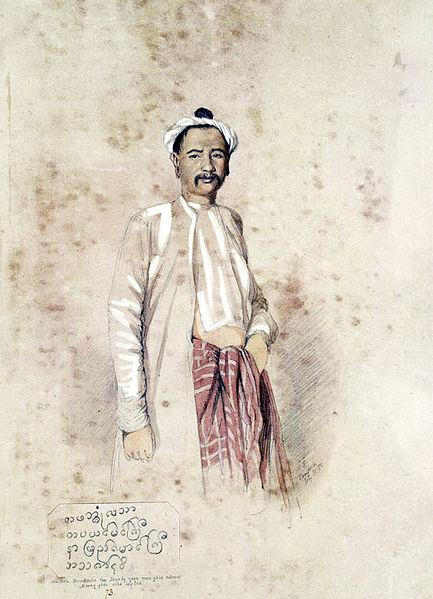

A watercolour portrait of the Myoza of Dabayin (Maung Gyi), commander of Burmese forces and the son of Thado Maha Bandula.

1852 - 20 December 1852

Second Anglo-Burmese War

In 1852, a second Anglo-Burmese war, briefer than the first, had led again to an unambiguous British victory and the loss of more Burmese territory. Whereas the first was the result of aggression by the Burmese as well as British expansion, in this one the blame was entirely with Calcutta, then the capital of the British Raj.

It started with an incident: the governor of Rangoon fined the captains of two British ships for alleged custom violations and there followed an ultimatum in which Lord Dalhousie, the governor-general of India, demanded that the Burmese rescind the fine and sack the offending governor. The Burmese government, aware of what might be in store, quickly accepted. But then the British naval officer on the scene, Commodore George Lambert (the “Combustible Commodore”), went ahead and blockaded the entire coastline anyway, without any additional provocation. Dalhousie, though furious with Lambert, then surmised that war was inevitable and decided to demand one million rupees, with the justification that this was the amount that the British had already spent preparing for war. Finally, without even waiting for a Burmese response, the British seized Rangoon and other port towns in the south. It was the first campaign of Garnet Wolseley (later Field Marshall Viscount Wolseley) who would go on to distinguish himself in battlefields from India to Canada, Africa and Egypt.

The Burmese were drawn into a war they neither wanted nor were ready for. The army was led by the lord of Dabayin, son of the Maha Bandula and a career military man. But despite an energetic resistance at Pegu, thirty years of technological advance on the British side and few improvements on the Burmese side meant that the defenders had little hope.

The fighting dragged on and effectively ended only when a revolution at the Court of Ava overthrew the incumbent king (King Pagan) and placed the prince of Mindon, a half brother of the king’s and the future builder of Mandalay, on the Konbaung throne. In the dark days of the second Anglo-Burmese war, when defeat was again staring them in the face, those inclined to face reality banded together around the 39-year-old prince, earning him the animosity of the more conservative and militant faction that was then in charge. Rumours circulated and, as British troops pushed north, Mindon fled north to his ancestral home at Shwebo and raised the standard of revolt.

Mindon was accompanied by his brother the prince of Kanaung as well as many armed retainers. More men were recruited and organized, and before long, along the banks of the Irrawaddy, they were able to smash the loyalist troops sent out against them. When they then appeared on the outskirts of Ava, at the head of their new army, their pennants flying against the low blue green hills in the clear November light, the nobility, not wishing for more bloodshed, changed sides. Two of the court’s most powerful ministers, the lords of Kyaukmaw and Yenangyaung, convinced the Household Guards to stand down. The gates were thrown open, and Mindon and Kanaung entered the great teak ramparts unopposed. It was more a coup than anything else, and put a new generation was in charge.

On 20 December 1852 the British East India Company defeated the forces of the king of Burma and annexed Rangoon and Lower Burma to their Indian empire, ending the second Anglo-Burmese war.

~Extracted from ‘The River of Lost Footsteps’ by Thant Myint-U

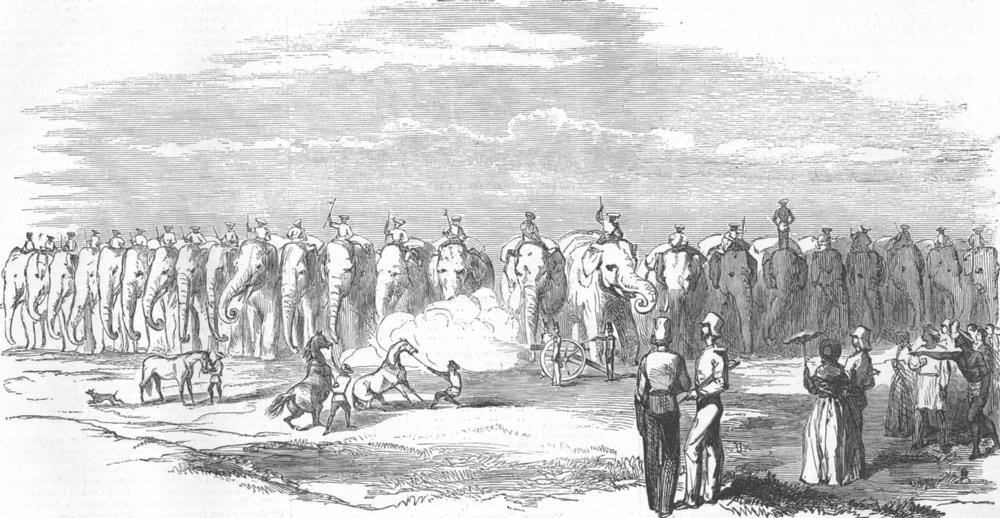

The black-and-white illustration shows British forces mustering their war elephants at Moulmein.

Explore more in Late Konbaung Myanmar and the English Wars (1824-1885AD)