Vice President Richard Nixon and Mrs. Nixon with President U Ba U at Government House, Rangoon 1953.

Chinese Nationalist troops in eastern Burma c. 1952.

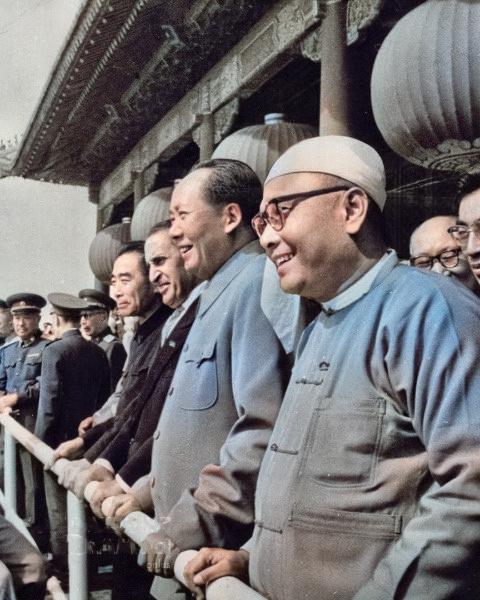

Prime Minister U Nu and Chairman Mao Zedong in Beijing, 1960.

General Ne Win and President Lyndon Johnson at the White House, 1966.

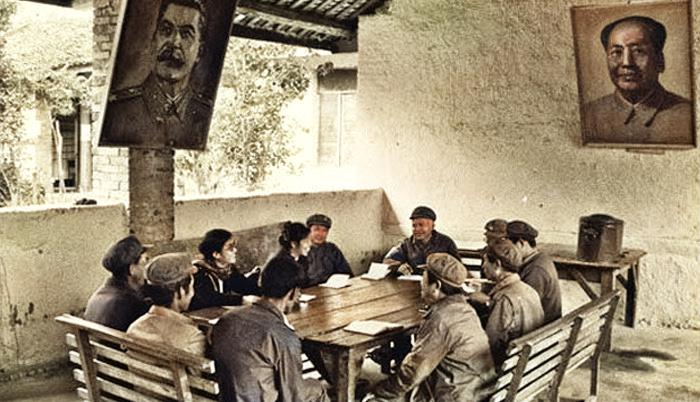

Communist Party of Burma in Pangsang c. 1975.

1946 - 1989

The embers of the Cold War

The past as prologue?

Burma became independent during the early years of the Cold War. In 1946, the United Kingdom decided to quit Burma. In 1947, the British government encouraged the Shan saophas (hereditary leaders) and other minority leaders to join and support a new Union of Burma. They did this in the hope that a unified Burma might fare better in the face of possible communist aggression. Over late 1949, the Chinese civil war ended with a communist under Mao Zedong. Around the same time, encouraged by the Soviet Union, the Communist Party of Burma launched an all out insurrection against the new Burmese government, seizing Mandalay and towns across the country.

Burma then had a fairly pro-Western position. The UK and other Commonwealth countries provided military assistance, flying in arms as well as advisers (Burma was also part of the Sterling area, which refers to the group of countries using the pound sterling as their currency or have their own currencies pegged to it.).

By the end of 1949, defeated Chinese Nationalist (Kuomintang or KMT) forces loyal to Chiang Kai-shek fled not only eastwards to Formosa (Taiwan) but also southwest from Yunnan into the Shan hills. By 1951, at least 10,000 KMT troops had taken over a large part of the eastern Shan states and by 1952, had penetrated to within 200 miles of Rangoon. This KMT occupation of part of the country, supported at least indirectly by Washington, infuriated the Burmese government of U Nu. The Burmese government was then facing not only a communist insurrection but also multiple other rebellions, notably by the Karen National Union (helped by Thailand), the Mujahideen in Arakan, and numerous other militia. The central fear was that the presence of the KMT, who were staging attacks from Burma into Yunnan, would lead to a Chinese communist invasion.

The Burmese government turned to the United Nations for help. Its disappointment with the UN by 1953 led both to a turn towards "non-alignment" and the build-up of its own military machine - the Tatmadaw.

U Nu's government tried over several years both to promote "non-alignment" and to stay friends with all the big powers. Premier Khruschev of the Soviet Union and Vice President Nixon of the United States both visited over the 1950s, as did Chinese leaders including Zhou Enlai, on many occasions. U Nu travelled himself to the US, USSR, and China, working to convince all sides that they had nothing to worry about from Burma's "neutral" foreign policy. The Burmese were extremely sensitive to anything that might provoke one power or the other. In 1953, when the US offered generous development assistance but on conditions that seemed to infringe on Burma's neutrality, the Burmese abruptly terminated all American aid.

General Ne Win, after his takeover in 1962, first saw the Americans as the bigger threat. By then the Cold War was at its height. Washington and Moscow had been on the verge of nuclear war over Cuba. The CIA was operating a "secret war" in Laos. The US was sending its first soldiers to Vietnam. General Ne Win feared assassination, as had happened in 1963 to South Vietnamese leader Ngo Dinh Diem. It was at this point that the US decided to win over the Chairman of the Revolutionary Council, despite his "Burmese Way to Socialism" was a rabid anti-communist and no friend of Beijing. US ambassador, Henry Byroade, was an ex-general who became good friends of both General Ne Win and his wife Daw Khin May Than. In 1965 members of the US Senate Foreign Relations Committee led by Senator Mike Mansfield visited the General and spent four days with him in Rangoon.

In 1966 General Ne Win travelled to Washington. It was the first and only state visit by a Burmese leader to America. The general received a military parade down Pennsylvania Avenue as well as a 21-gun salute on the lawn of the White House. In his meetings with top American leaders, including President Lyndon Johnson, he convinced them that Burma - though formally neutral - could be a bulwark against communism in southeast Asia. The Americans, in turn, convinced General Ne Win that they were his friends. He agreed to secretly restart US military aid. Other assistance, including from the World Bank and IMF was also resumed. American allies like the West German Chancellor Kurt Kiesinger and Japanese Prime Minister Eisaku Sato visited Rangoon as did many senior British figures including Lord Louis Mountbatten.

As relations with the West improved, relations with China veered towards disaster. In 1966, the Cultural Revolution in China was in full swing. Beijing was also extremely wary of improving Rangoon-Washington ties. In May 1967, pro-communist ethnic Chinese students in Rangoon demonstrated, wearing Mao badges and shouting Cultural Revolution slogans. Within days, counter-protestors turned on the students, leading to violence that left dozens dead of ethnic Chinese dead and hundreds more wounded. The Chinese embassy was attacked and one Chinese aid official killed. The Burmese army and police did little to stop the violence. Beijing was outraged. By July, Peking Radio was openly calling on the Burmese people to raise up against the "Ne Win Fascist Dictatorship".

The Communist Party of Burma was then very weak. After nearly 20 years of fighting, it was down to a few thousand men holding out in the Pegu Yomas. In late 1967, the Burmese army increased its operations against the insurgents, leading to the assassination of communist leader Thakin Than Tun. The original communist revolt was nearly finished.

But then, in January 1968, heavily armed communist forces under the command of General Naw Seng, a British-trained Kachin World War Two hero, crossed into northern Shan state from Yunnan. Within weeks, they had established a new "liberated area", along the Chinese border. Within a few years, this liberated area included all the Wa Hills and most of the eastern Shan states. Communists who had been living in China since 1949 now headquartered themselves at Pangsang. These new Beijing-supported communists were able to strike up to Mogok and Maymyo in the west and down to the Thai border in the south. Though the Politburo were almost all ethnic Burmans, the vast bulk of the communist army were local recruits - Kokang, Wa, Kachins, and others, as well as Chinese "volunteers". The Burmese army, with new American support, and also with the support of local Kokang and Shan militia were barely able to keep the communists in check over two decades of heavy fighting that would follow.

Over the 1970s, General Ne Win attempted to repair relations with Beijing. With the end of the Cultural Revolution and the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, relations did begin to improve, leading to an historic visit by Deng Xiaoping in 1978. Beijing's assistance to the Communist Party of Burma began to wane but never fully stopped.

In 1989, as the Cold War came to an end, the Communist Party of Burma collapsed through an internal rebellion. Its forces fractured into several different armed organizations, with the main part becoming the United Wa State Army. That same year, ceasefires were agreed between Rangoon and these new ex-communist armies. Burma's socialist and isolationist policies were at the same time abandoned. At exactly this same time, however, the West moved away from Burma, as part of an effort to encourage democracy. China then stepped into the breach, strengthening economic ties in this new period of capitalism. Now, over 30 years on, the ex-communist armies remained fully entrenched on the Sino-Burmese border- the remaining embers of the Cold War.

The "American Welcome" video is part of the digital archives at the LBJ Presidential Library of US President Lyndon B. Johnson. It documents General Ne Win's visit to the United States in September 1966; including the 21-gun salute he received, warm remarks by both General Ne Win and President Lyndon B. Johnson, and Ne Win's trip to New York to see United Nations Secretary General, U Thant.