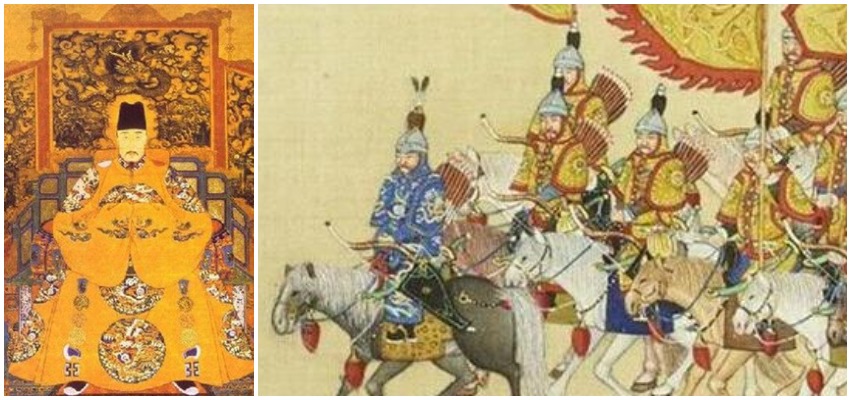

Qing General Dong defeating Wu Sangui's later rebellion in 1677

1646

The Flight of the Ming Prince

room China

From the west it was Mughals, moving in against the borders of a fast-shrinking Arakan. But to the north and east, it was an ever more vigorous China, pressing down hard, right into the heart of Burma.

In China in 1646, after the fall of the Yangtze Valley and the eastern coast to the invading Manchu armies, the 23-year-old prince of Gui, the last surviving grandson of the Wanli emperor, became the last and desperate hope of the Ming imperial cause. For years, China had been at war. The Manchus under their leader, Nurhaci, had unified the Tungusic-speaking nomads along the Amur River valley, first threatening the northern border regions and then taking Peking in 1644. Their new dynasty, the Qing, then moved down into China proper, scattering the loyalists of the old regime. Until the republican revolution of 1911, China would be ruled by these milk-drinking, cheese-eating, one-time nomads of the far north.

The prince of Gui’s father was the seventh son of the Wanli emperor, and the young prince had been brought up among the sybaritic pleasures and strict hierarchies of the Imperial City. He was now on the run, fleeing first to his ancestral estates in Hunan, central China, and then to the southwest near present-day Hong Kong. It was there, among the limestone cliffs of the Pearl River delta, that his fugitive court named him the Yongle emperor and rightful heir to the 300-year-old Ming Throne.

As such, he became a lightning rod for the growing resistance to the Manchu occupation. For the next year and a half the prince of Gui and his men trekked across the far south of China, along the borders of Vietnam, and then southwest into the tribal regions of Guangxi. The long flight from Peking meant that the self-styled imperial court was far from what a proper Ming court should be, and one contemporary observer described it as being filled with “all manner of betel-nut chewers, brine-well workers and aborigine whorehouse owners.” But it rallied the die-hards and, for a while, kept the advancing Qing rulers at bay.

By early 1650, Qing forces had managed a breakthrough, crushing opposition in areas that had declared their support for the prince of Gui and launching a direct attack on his southern bases. In this offensive the Manchus relied on Ming Chinese generals who had defected more than a decade before, and these generals pursued the loyalists farther and farther southwest until, in 1658, they made their last stand at the little border town of Tengyue and then slipped over the hills into the kingdom of Burma.

The prince of Gui entered Burmese territory in the hills of the northeast, part of a great arc of upland areas only indirectly under Ava’s rule. Here the vast majority of the local people were not Burmese at all but spoke instead a variant of Thai or Siamese, know in Burmese as Shan. Some of these principalities were of considerable size. Chiangmai and Kengtung, for example, were the size of modern Belgium or Wales, while others were little more than a collection of impoverished mountain tracts. In the early years of the Ming dynasty many of these principalities, perhaps the first in Southeast Asia to acquire knowledge of guns and gunpowder from the Chinese, had expanded aggressively to the south, overrunning Ava and the Burmese plains. More recently, however, they had adopted a more modest posture; in varying degrees their rulers, or saophas, maintained a tributary relationship with the Court of Ava, providing daughters for the royal harem and gifts of silver and horses for the king.

When the prince of Gui arrived with over 700 followers at the border post of Momein, he met first with a local Shan chief, requesting refuge in Burma and offering his sovereign a not inconsequential treasure in gold. The king at the time, Pindalay, agreed. He welcomed the prince and constructing a residence for him at Sagaing, just across the Irrawaddy River from Ava. But it turned out that the prince was only the first of many thousands of Chinese now streaming across the border; some refugees, other bandits and freebooters who had taken advantage of the anarchy in southwestern China and now sought to terrorize the Burmese countryside. These marauding bands declared their allegiance to the prince of Gui and asked their leader to leave Sagaing and join them. They seized the towns of Mongnai and Yawnghwe in the east and routed the army Pindalay sent to try to stop them. Monasteries were burned. Whole villages were looted, and men and women were taken captive and carried off. Soon they were at Tada-u, just outside the gates of Ava itself, where only the tough resistance of the king’s Portuguese artillery managed to stave off their advance.

The prince of Gui was deeply apologetic. He insisted that he had nothing to do with what was going on in his name. Blame fell first on the Burmese king. Pindalay was a weak ruler, the son of a concubine rather than a queen, and thus enjoying less than normal legitimacy. He had all along been manipulated by an increasingly powerful noble class, and this nobility now turned against him, making him the scapegoat for the troubles and replacing him with his younger brother the prince of Prome. It was the hereditary officer corps in the army that had first agitated for his removal. They had seen the devastation in the countryside firsthand. Many had families in the irrigated lands to the south of Ava and, when food became scarce in these lands as a result of the invading Chinese, they had appealed for their king’s help. Instead Pinadaly had allowed his favourites and concubines to sell rice to the hungry at exorbitant prices. The army men then appealed to the royal ministers, who were quick to replace Pindalay with his half-brother Prome.

Prome was a stronger monarch, and he soon turned his attention to the increasingly nervous prince of Gui. He suspected the refugee emperor of conspiring with the Chinese bands all around them and summoned the prince’s followers to the Tupayon Pagoda at Sagaing. Prome said he wanted them to take an oath of allegiance. They refused until the saopha or lord of Mongsi, whom they trusted, agreed to be there as well. But it was a trick. At the pagoda the lord of Mongsi was taken away. And royal troops moved in to encircle the Chinese. The Chinese reached for their swords and then were shot down by the king’s musketeers. Those who survived the shooting were beheaded. The prince of Gui became even more nervous.

In 1662, four years after the prince had first entered Burma, the Great Chinese general and viceroy Wu Sangui marched into the kingdom at the head of an enormous imperial force, 20,000 strong. They came straight down the mountains, halting only a few miles from Ava and demanding the surrender of the Ming prince. Wu Sangui was then 50 years old. He had been a senior Ming commander but had switched sides and had opened the gates of the Great Wall of China to the Manchu armies of the north. In 1673 he would switch sides again and rebel against the new Qing dynasty. But for the time being, he was on the side of the Manchus and had taken as his wife the sister of the new Manchu emperor.

It was said that Prome wanted to fight but that his ministers told him to get rid of their troublesome guest once and for all. And so, the prince of Gui and his family were handed over as prisoners. The prince was now 38 and his son was 14. They were taken to Kunming in Yunnan and strangled to death in the marketplace with a bowstring. Another son apparently died in Burma and is buried at Bhamo near the Chinese border. His wife and daughters were taken to Peking. During their days in Burma the whole family had converted to Roman Catholicism, under the influence of a Jesuit priest at Ava, and had taken the Christian names of the fallen Byzantine house: the prince of Gui’s son had become Constantine, his mother, the empress, was named Anne, and the other princesses were named Helen and Mary.

The upheavals weakened the now nearly two-centuries-old dynasty. But the kingdom stayed together, absorbing the blows of the Chinese incursions without breakup or revolt. This was in large part due to the reforms that had taken place. Like all societies in Southeast Asia at the time, the key to economic power was not so much land as people; there was always a dearth of people. Wars were waged to capture people as well as loot, and government was about the proper management of the king’s men. All this was improved and systematized. And the image of the empire, of Bayinnaung’s exploits, and of the more distant memories of Pagan and Prome remained. When the dynasty finally fell, the new royal clan would accept the old traditions, turning only later toward radical reform when confronted with disaster at the hands of an entirely new foe, the English East India Company.

~ Adapted from The River of Lost Footsteps by Thant Myint-U