British Burma (1826-1942)

For over a hundred years, Britain ruled parts of what is today Myanmar, shaping every aspect of the country’s politics, economy and society.

Far from being a static period of stability, British Burma was marked by change and upheaval. As it had done in India, the colonial power uprooted the ruling dynasty: the last Mughal emperor of India was secretly buried in Rangoon, while the descendants of Burma’s last king ended up living in penury in a slum in Kolkata, India.

It was a time of searching for new identities and political systems, with various forms of resistance to British rule from the armed uprisings during the early “pacification” of Upper Burma to the heated politics and protests of the decades prior to World War Two. The political landscape was peopled by British-educated Burmese politicians and home-grown activists inspired by Ireland’s Easter Rising of 1916. The first-ever election was held in 1922 and, a decade later, it was decided at the Burma Roundtable Conference in London that Burma would separate from British India – perhaps the single most important decision in Myanmar’s 20th-century history.

Through the empire and technological advancements in transport, Burma became connected with the rest of the world like never before: thousands of Chins, Kachins, Burmans and Karens served in World War One and Rangoon was a key stop on the world’s first long-haul commercial flights. Until the Great Depression struck, business boomed with big profits from exporting rice, teak and oil – at one time the Burmah Oil Company was one of the biggest multinational companies in the world.

In 1927, The Chilean poet Pablo Neruda lived in Rangoon and later encapsulated these heady times in a poem describing the capital of British Burma as “a city of blood, dreams and gold

Burma in 1938

Taken in 1938, this photograph of Rangoon Harbour captures the calm at the centre of a storm. The tumultuous rumblings of 1938 foreshadowed elements of the country's future: the new quasi-democratic constitution and appeals for constitutional refor; more political freedom; hotly contested elections and political infighting; calls to "protect race and religion"; economic uncertainty and extreme income inequality; Buddhist-Muslim violence; increasing strategic importance between China and India; and the rise of extreme nationalism.

Read MoreIn memory of Bo Aung Gyaw

On 20 December 1938, University student "Bo" Aung Gyaw was killed by police on Sparks Street (now Bo Aung Gyaw Street), while dozens of other Burmese demonstrators against colonial rule were wounded as they attempted to march around the Secretariat. Bo Aung Gyaw was the first martyr of the nationalist movement and tens of thousands of people attended his funeral a week later - the route was so thick with mourners that it took four hours for the cortege to...

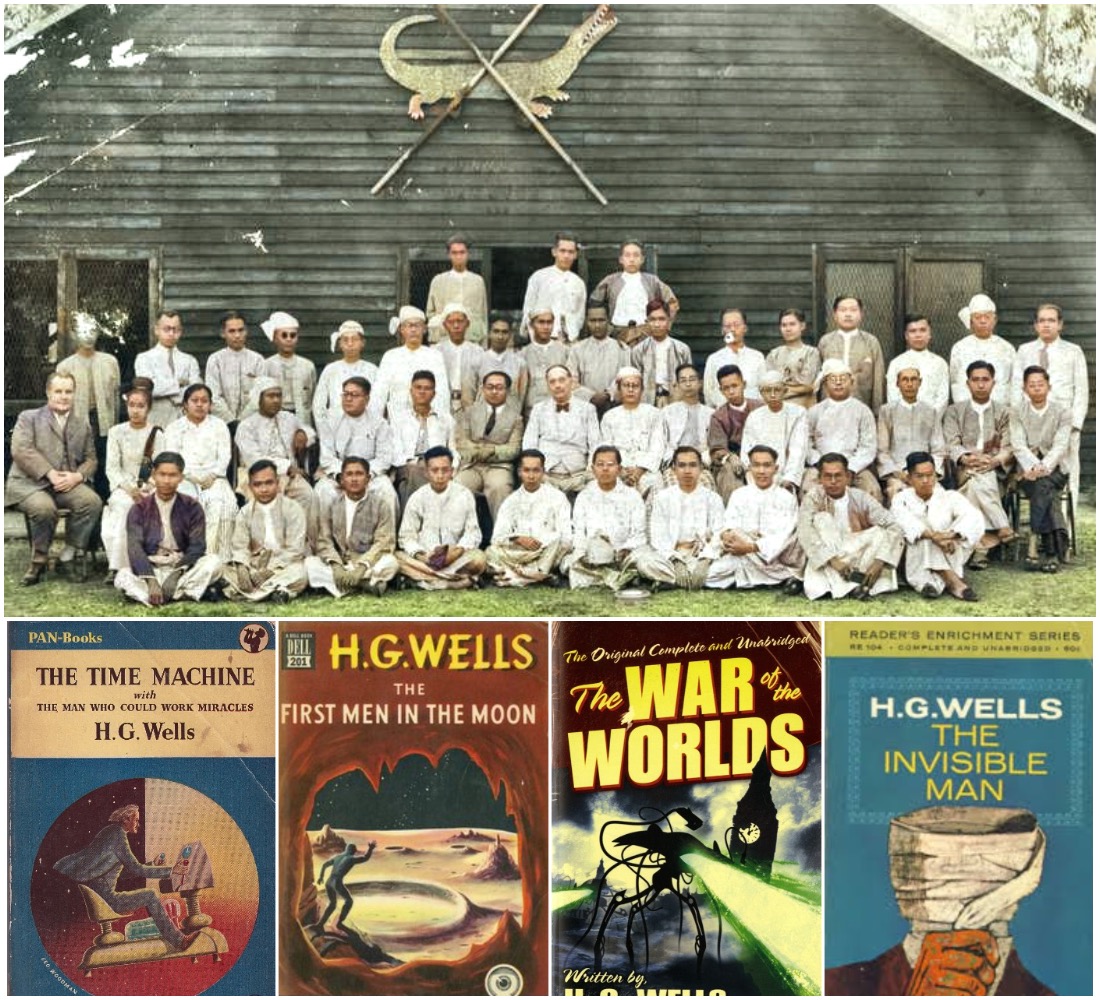

Read MoreHG Wells in Rangoon

H. G. Wells visited Rangoon in July 1939. He was then 72 years old and one of the most famous writers in the world. The author of such classics as The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds, he wrote nearly a hundred other books over his lifetime. He is today known (together with Jules Verne) as the father of science fiction. With his deep belief in the idea of a world community, H. G. Wells was a supporter...

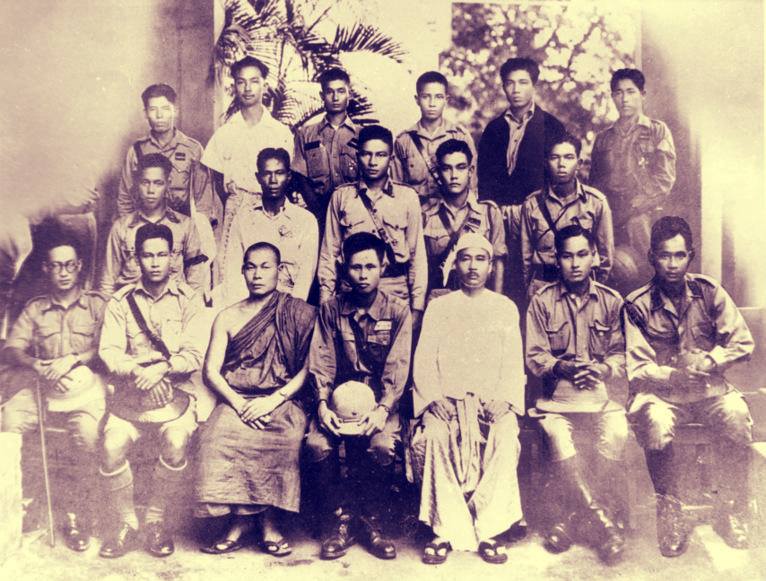

Read MoreColonel Suzuki Keiji of the Minami Kikan

Japan's ties to the Myanmar armed forces go back to the very founding of the Burma Independence Army in 1941. The pivotal figure on the Japanese side was Colonel Suzuki Keiji of the Minami Kikan (a sort of special operations directorate), who first recruited General Aung San and trained the now legendary Thirty Comrades. Colonel Suzuki and his Minami Kikan fellow-officers came to associate closely with Burma's desire for independence and were at times distrusted by their own Japanese superiors....

Read More